The Tragedy of Jason Voorhees: How 3 Sequels to a Low Budget Slasher Film Created an All-Time Great Film Trilogy

Cinema has had its share of classic cinematic trilogies. Some cinema stories are crafted as trilogies from the outset: Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings (2001-2003), Robert Zemeckis’s Back to the Future (1985-1990), Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight saga (2005-2012), each of the three Star Wars trilogies, and Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours films (1993-1994). And then there are three consecutive films in cinematic franchises that may not have been designed to comprise a trilogy, but over time have become recognized as one: Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead (1981-1992) and Spider-Man (2002-2007); Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather (1972-1990); and Steven Spielberg’s first three Indiana Jones films. It is in this latter category that three Friday The 13th films, namely Part 2, Part 3, and The Final Chapter, not only fit but very much belong. Not only do these films create the classic three-part beginning, middle, and end of one of cinema’s most iconic characters, they do so better than most. In fact, they tell an epic anti-hero story arc that is as cohesive and coherent as that of Anakin Skywalker or Michael Corleone. They are the “Tragedy of Jason Voorhees.”

Each of the three sequels included key world-building elements that happened to fit together in such a complete way that, in hindsight, it seems as if they had been planned from the start. Part 2 set the stage by re-introducing an all-new Jason Voorhees, creating a “legend” surrounding him, setting the timeline of key events, and filling in details of the “world” in and around the lake where he operated. Part 3 built upon the character by introducing the hockey mask (and thereby changing popular culture forever), and changing the manner in which Jason was seen throughout the film by way of a bolder modus operandi. The Final Chapter lived up to its billing with a worthy final confrontation and end to the saga. It is important to note that these three sequels were essentially piecemeal projects that moved forward quickly only after the financial success of the immediate predecessor. Financed by independent producer Georgetown Productions and distributed by Paramount Pictures, the films had no formative design to serve as a trilogy, which makes the accomplishment even more impressive.

How to Make a Sequel

Of course, there are no sequels without a successful first film. The original film was released on May 9, 1980, grossing almost $6 million in 1,100 theaters on its opening weekend (Box Office Mojo). “Thoughts of a Friday the 13th sequel began occurring to Georgetown Productions immediately upon the film’s prosperous opening week,” with the goal of releasing the following year (Burns, 12). With such a quick turnaround, several of the filmmakers (director Sean Cunningham, and special make-up effects artist Tom Savini) were unavailable. Returning from the first film were Steve Miner (associate producer/unit production manager on the first film) stepping up as producer/director, and Ron Kurz (who was uncredited in the original film) writing the screenplay. There were two key additions to Part 2 of individuals who would remain for all three sequels. Frank Mancuso, Jr., was brought on as a gofer and later credited as an associate producer for Part 2 and a producer for the next two films. His father, Frank Mancuso, Sr., was rising as an executive at Paramount Pictures at the time. Lisa Barsamian, the daughter of Georgetown Productions’ Bill Barsamian, served as the production manager for Part 2 and ultimately executive producer for all three sequels. Among other things, Mancuso and Barsamian worked together to ensure that Part 2 would remain on budget—no small priority for Georgetown Productions or for Paramount (Bracke, 56). It logically follows that there would have been no Part 3 if Part 2 was not a box office success.

While it made business sense for the films to continue, in a narrative sense, that would be a bit of a challenge. Pamela Voorhees, the killer in the original film, was most certainly unavailable to make a return, given the fact that she had been decapitated by Adriene King’s character Alice, the lone surviving camp counselor. The solution lay in finding a way to pass the torch. Shades of Bilbo Baggins’s adventures in The Hobbit setting up Frodo’s epic adventures in The Lord of the Rings, Friday the 13th expanded from a single tale to a veritable mythological world that spanned years and generations of characters. That expansion begins with the character Jason becoming the prominent horror character, meeting revenge on those who enter his woods.

The continuation of the story, in and of itself, was not without a continuity question. Part 2 and the sequels that followed set aside the horror community’s canon-esque question of whether Jason actually survived the drowning in the first film. Steve Miner obviously approached the story as if he had. Original Friday the 13th writer Victor Miller, on the other hand, believes Jason drowned, and should have remained dead (Foster). Jason’s survival raises a follow-up question of why, if he did survive, did his mother fly into a homicidal rage years later believing that he had died (as depicted in the first film). In fact, continuity errors arose with each additional film, especially given the fact that story-wise, the three sequels occurred over several days, one right after the other. For example, moving from Part 2 to 3—what happened to Jason’s long hair and brutal shoulder machete injury that was depicted at the end of Part 2; and moving from Part 3 to The Final Chapter—what happened to the stab wound in Jason’s leg and the wound to his hand, neither of which appear at all in the fourth picture? Despite these questions, the films overcame any such errors relatively easily. Fortunately, the errors were relatively minor (it’s not like they had Jason Voorhees mouth-kissing a character later revealed to be his sister or anything), and the solution was to apparently ignore them. In fact, instead of attempting to (over) explain any inconsistency from the original away, Part 2 effectively rendered it moot by way of making what happened to Jason the stuff of legend. This was accomplished via a campfire scene where head counselor Paul shares the legend of Jason with the trainee counselors just before his assistant head counselor pranks the others by scaring them. This embedded narrative accomplishes two purposes: within the story itself, Paul attempts to dispel any potential temptation of the counselors to explore the remains of Camp Crystal Lake; and, more importantly, for the audience it serves the much more important role of recasting the series to being Jason-centered.

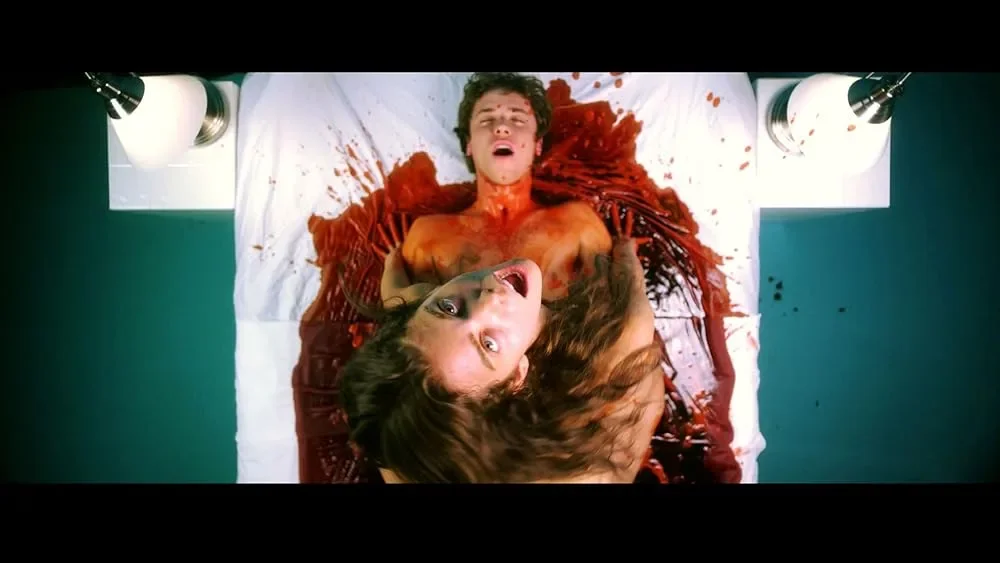

Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981) image via IMDb.

Next, Part 2 built the new Jason character. He was older now, with the majority of the second film occurring five years after the first (which itself occurred years after Jason “drowned”). However, the opening scene in Part 2 occurred only two months after the events of the first film and involved Jason seeking out Alice and killing her. Then, Jason returned to his woods, and went quiet. This two-month jump then five-year jump from the original to Part 2 both allowed for the legend of Jason to rise, and for Jason to become such a powerful killer moving forward. Gone were the days of the misfit who couldn’t swim, and in his place was a large and strong masked killer, one who murdered his victims in brutal ways. This approach is distinctly different from the first. In the first film, Pamela Voorhees did not wear any kind of mask. She used guile and her own unthreatening appearance to get close enough to the victims to affect the kills. In fact, her identity as the killer was also unknown until the final conflict with Alice at the end. Moving forward, that element of mystery would be lost. The question of the killer’s identity only works if the audience is in the dark. Once the audience knows, then the presentation of the antagonist killer would have to change. Part 2 dispelled any mystery as to the identity of the killer by essentially having one of the leading characters explain to the audience that it is, in fact, Jason Voorhees who now haunts the woods in and around Camp Crystal Lake—and it worked. Part 2 was a financial success, and, according to boxofficemojo.com, was the 15th highest-grossing film in the domestic box office for 1981. Naturally, it was time to make a sequel.

There were some questions among those associated with the films as to what creative direction Part 3 would follow. Speaking with FANGORIA magazine, Steve Miner explained the thought process, “I spent a lot of time developing a number of different storylines and approaches that would be a breakaway from the other films,” including focusing on Jenny, the survivor from Part 2. Ultimately, and wisely, the decision was made for the story to stay the course, with one exception. Part 3 was filmed and released as a 3D picture. This was a bold move, as the renewal of 3D pictures at that time did not include many strong box office performers, with Comin’ at Ya! (a Spanish-American production distributed by Filmways) and Charles Band’s Parasite (distributed by Embassy Pictures) being the other “big” releases that year. While 3D films thrived in the 1950s, there had not been much in the way of advancement since, either in terms of technology or exhibition.

As Bob Martin, reporting for Fangoria magazine, observed when he visited the set of Part 3, “The added fact of 3D raises some new questions: since the 3D trend began, we have yet to see a 3D feature released that comes close to matching the technical qualities of the better 3D films made a quarter of a century ago. We’d been told that the Marks system had been chosen for the film. A single-lens prism system developed for use with Mitchell cameras, and later adapted for the Arriflex (as used for FT III), the Marks 3D system is reputed to be particularly difficult to use properly. ‘We looked at all the systems when we started, and the consensus of opinion was that they were all difficult,’ says Miner. ‘There’s no state of the art where 3D is concerned, because all the systems are from backyard inventors are piecing them together.’” New York Times film critic Janet Maslin noted, “As in each of the other recent 3D movies, of which this is easily the most professional, there is a lot of time devoted to trying out the gimmick. Titles loom toward you. Yo-yos spin. Popcorn bounces. Snakes dart toward the camera and strike. Eventually, the novelty wears off, and what remains is the now-familiar spectacle of nice, dumb kids being lopped, chopped and perforated” (Maslin). The Amityville and Jaws franchises would follow suit in 1983 to mixed results. It was a gamble, one that worked, but also served an important role in the story of Jason Voorhees’s character. Part 3 represented Jason in a much more aggressive form. Like a predatory great white shark, he moved about Higgins Haven (the setting for the story) confidently and openly, going from one kill to the next. He dispatched a motorcycle gang in broad daylight, fired a spear into the eye of a character as she asked him questions trying to figure out who he was, and nearly chopped a guy in half as he walked along inverted while doing a handstand. In terms of production, these events lent themselves to the 3D aspect of the film. In addition, in a narrative sense, this aggression showed Jason reaching his zenith: He is in his strongest form here (conveniently overlooking the absence of the machete wound that nearly cut his torso in half at the end of Part 2 [come to think of it, that must have been a really sharp machete]). The dark king has assumed his throne, with the hockey mask horror crown firmly on his head.

Part 3 opened on Friday, August 13, 1982, in 1,079 theaters and was the number one highest-grossing film that weekend. It earned the 20th highest domestic box office receipts for the year (actually outperforming Part 2), and was the second-highest horror film (only behind Poltergeist). Not surprisingly, it was time to make a sequel.

For the fourth film, Joseph Zito was hired to direct and Tom Savini returned to do special make-up effects. At the time, there was a sense within the crew that The Final Chapter really was the final chapter. As Savini himself noted, “We did so much damage to Jason that I don’t see how they can bring him back, and I really don’t think they intend to. There was a moment, on the last day of shooting; we shot the scene where the police arrive, and Jason’s body is lying there. We finished the shot, and Joe Zito said, ‘Jason’s gone. He’s dead…’ There was a long pause, and Frank Mancuso, who produced all four of the films, said, ‘Yeah… it feels kinda odd to know he’s really gone…’” (Martin, 59).

With The Final Chapter, the “Tragedy of Jason Voorhees” ends in a manner worthy of Shakespeare: Jason falling at the hands of his heir apparent, new character Tommy Jarvis. There are clear parallels between the two. Tommy, played by Corey Feldman, was presented somewhat as a loner (one who happened to be talented with making masks and scary/creature effects); he had no father figure in his life; and the people to whom he was closest were his mother and his sister Trish—who were always close at hand whenever he was outside of his home. He was also so needy and desperate for attention that when he and Trish bring Rob, a local hiker who happened to also be hunting for Jason, into the house, Tommy immediately pulls Rob into his bedroom to show him his collection of creatures, masks, and effects. Prior to their return to the house, Rob had just shown Tommy how to fix their car that had stalled in the woods. Tommy also has a pubescent fascination with sex, as seen in the scene in which he spies on the lovers in the other cabin through his window, only to retreat and feign slumber when he senses his mother’s entry into his room. Also, when Tommy and Trish notice the visitors to the cabin next door are skinny dipping, Trish immediately tries to shield Tommy from seeing them and then pulls him away. Jason, for his part, later kills Rob, eliminating the only person who (briefly) came close to serving as any kind of father figure to Tommy. The pièce de résistance to Jason’s saga is the final battle where it is Tommy who kills Jason. In fact, Tommy “becomes” Jason during the battle, shaving his head to mimic how Jason looked when he (almost) drowned as a boy. Tommy ended The Final Chapter, and thus the “Tragedy of Jason Voorhees,” by doing exactly what Jason had done to open Part 2: He killed the person who killed his mother. As is the case with many great tragedies, the circle was complete.

Notwithstanding the fact that there have been eight other films (four Friday the 13th films distributed by Paramount Pictures between 1985–1989, three Jason films distributed by New Line Cinema between 1993–2003, and a 2009 updated version of Friday the 13th released by both New Line and Paramount), The Final Chapter was the end of the Jason Voorhees character. By the time he did return, he was no longer human Jason (who could sustain injuries, bleed, and ultimately be killed), but was zombie Jason—an indestructible, undead Terminator character who could not be killed, but only contained (or, for a very brief and fleeting moment in time, magically de-aged by the toxic waste that flows through the sewers of New York City at night).

-

“Domestic Box Office For 1980.” Box Office Mojo, www.boxofficemojo.com/year/1980/?ref_=bo_yl_table_45. Accessed 28 Nov. 2024.

Bracke, Peter M. Crystal Lake Memories: The Complete History of Friday the 13th, Titan Books, 2006.

Burns, James H. “Friday the 13th Part II.” FANGORIA, vol. 2, no. 12, 1981, pp. 12–15, 64–65.

Foster, Tom. “Why Original Friday the 13th Writer Believes Jason Voorhees Was Done Wrong.” TV Over Mind, 25 May 2021, www.tvovermind.com/why-original-friday-the-13th-writer-believes-jason-voorhees-was-done-wrong/. Accessed 6 Dec. 2024.

Martin, R.H. “Savini and Friday the 13th – The Final Chapter: The Master of Crimson Effect is Back! Jason Dead ?!??!” FANGORIA, vol. 1, no. 36, pp. 56–59.

Maslin, Janet, “Friday the 13th Part III – in 3-D opens.” Review of Friday the 13th Part III, directed by Steve Miner. New York Times, 13 Aug. 1982, p. C4. www.nytimes.com/1982/08/13/movies/friday-the-13th-part-iii-in-3-d-opens.html.

Article by Arthur Brooks

Arthur Brooks is a judge for the Pittsburgh Moving Picture Festivals. In his spare time, he is reading scripts, watching movies, and trying to remember how to properly format footnotes.

![[Movie Review] Don’t Trip (2025)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d3e481bc5a6e40001b215a8/563ae9c8-9ce1-468e-a60c-413ca76d61c8/dont-trip-poster.jpg)

![[Movie Review] Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey 2](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d3e481bc5a6e40001b215a8/b4fd5bad-fcb1-4671-840d-209acd55de9d/pooh-bah-2.jpg)

Throughout the decades, slasher film villains have had their fair share of bizarre motivations for committing violence. In Jamie Langlands’s The R.I.P Man, killer Alden Pick gathers the teeth of his victims to put in his own toothless mouth in deference to an obscure medieval Italian clan of misfits.