In Defense of Gross Girls: Why Horror Needs Unpleasant Female Protagonists

Introduction: The Horror of Undesirability

The depiction of the undesirable castaway as horrific monster is a tale as old as Frankenstein, and in the centuries that have passed, this archetype has taken many different shapes, and we can thank new applications of abjection for that. When a character “transforms the perceived ‘normal’ body into a negatively exceptional and/or painful version of itself,” whether it is the body of another or their own, the audience is forced to reckon with why we are so disturbed by the actions (Aldana Reyes 393). Is it because of the violent nature of the mutilation, or is it because of the repugnant visage of the human body?

This theory grows more complicated when the characters in question, often played by traditionally attractive actresses, are made to be ugly in their performances. The physical disruption and destruction of the body creates tension between what it means to be a girl or a monster in the horror genre. Body horror, therefore, is an excellent space for authors, filmmakers, and other creatives to “experiment with horror, the female form, and issues surrounding women’s bodies and bodily autonomy” due to its speculative nature and unashamed exploration of the feminine grotesque (Rapoport 620). Ugliness and grossness, despite being subjective terms, are tethered to body horror in that they subvert the traditional expectations of what we are to do with our bodies. Therefore, girls who embody these characteristics are monstrous before they even act on the violent urges they carry inside.

When we encounter scenes “where the foulness of woman is signified by her putrid, filthy body,” we experience a dissonant affect, disgust as opposed to terror (Creed, “Horror and…” 74). The female body is reduced to a grotesque object, and when woven with the nuance of conventional beauty or the burgeoning horrors of post-adolescence, we are confronted by the gross girl: someone we are repulsed by but cannot help but root for. The application of these traits to young female horror leads, in turn, adds monstrous nuance to these protagonists, whose disdain for the human condition compromises their girlhood.

The Female Mutilator as the Ultimate Gross Girl

There is a growing trend of “women who embrace violence as a refusal of victimhood” in postfeminist cinema, but the female mutilator trope is more nuanced than that (Fradley 214). Per my definition of the female mutilator archetype, these girls “have ... experienced trauma ... prior to the start of the story, work to heal their loneliness and isolation through the destruction of others and the eroticization of viscera, and they are completely unaware of the severity of their actions until it is far too late” (Stopenski 10). When a female mutilator is confronted with the consequences of her misguided actions, she does not perceive them as violence. Instead, she uses it as a bid for a connection, a way to engage the world around her. In her eyes, any attention is good attention.

The female mutilator struggles to see how to escape her abjection in order to continue living her grotesque life. She “is constantly beset by abjection which fascinates desire but which must be repelled for fear of self-annihilation,” where her fixations on repulsive hobbies and refusal to conform complicate her need to self-destruct (Creed, “Horror and…” 71). It is not that the female mutilator is a masochist—quite the opposite, in that she engages in such sadistic acts—but she acknowledges that experiencing pain and isolation keeps her human. The primary tenet of this trope is of a girl who destroys by mutilating, breaking down, and destroying bodies that are not her own. By remaining a socially unacceptable creature while executing her murders, disassembling her prey even after they have died, she almost affords herself a bit of safety in being on the outskirts. In being abject, she does not have to grow up quite yet, still bound to her naive but violent impulses. At her core, she has no idea she is a monster, and so has no intent to change her behavior.

In my previous scholarship, I iterate that other characters in cinema “recognize [the female mutilator] as the villain, she recognizes herself as a victim, and the audience recognizes her as something in between,” a painful duality that positions these girls in a realm of undesirability (Stopenski 12). Based on that notion, Fradley’s earlier critique doesn’t quite fit for this archetype. The female mutilator does not see herself as an agent of evil, nor does she see herself as something worth saving. Contemporary feminist horror shows that “abjection can lead to the rejection of patriarchal forms of visuality and the reconstruction of a feminist visual language,” so the female mutilator as a trope is slowly rewriting what a female antihero can look like in the genre (Creed, “Queering…” 112). If we apply that framework to the developing female mutilator, it only makes sense that young women would utilize physical markers of postfeminist rhetoric, bodily rejections of femininity, to actualize their place in their universe. The easiest way to do this is to alter the appearance to something ugly, a way for the character to show the world that she is non-threatening, even though we, as an audience, know that is not the case.

Hell is a Teenage Sociopath: May (2002) and Excision (2012)

May with her creation “Amy” in May (2002).

The “emphasis on young women's everyday gendered discontent ... in teen horror films” causes a frustration with being female that often complicates the protagonist’s view of the world around them, especially if they don’t adhere to traditional models of femininity (Fradley 209). Young women like May in Lucky McKee’s 2002 film of the same name and Pauline in Richard Bates’s film Excision (2012) follow the female mutilator archetype, unable to extricate their perverse actions from their desire to be wanted, victims to the dominant culture. Both are social pariahs in their respective worlds: awkward, plain, and privy to horrific musings. Though they have different upbringings—May is brought up by a poor single mother, while Pauline is from a moderately wealthy two-parent household in suburbia—these female mutilators are outcasted for their peculiarities well past puberty. Bullied for their strange nature and fascination with the macabre, the two have very distinct paths leading to a similar terrifying end.

May’s compulsions manifest out of a desire for friendship and love. A gentle soul at heart, she trusts those around her too quickly and fixates on those who exhibit an interest in her, whether platonic or romantic. May’s personality is more awkward than anything, not a malicious figure by any means. When it comes to romance, too, she does make some connections, albeit shallow ones, where she is far more invested than the other parties. May is pursued by men and women alike and uses the body parts of both genders to craft her perfect friend, “Amy.” By rearranging the letters of her own name to name her creation, May affirms that no one will love her the way she needs them to, so she must create that figure herself. At the root of her mutilation of others is a yearning, a desire to be loved that she is unable to attain organically.

There is an element of campiness at the close of the film, with “Amy” putting her arm around May, a cheeky call to the audience that maybe May was not so crazy after all, but its affect is not to make us laugh: It is to make us pity May, that she was so deranged by loneliness that she imagines this disembodied sack of parts showing her tenderness. If we operate under the belief that “monstrosity itself is made manifest in the flesh and bone surfaces that collide with the affective materiality of other bodies not built through modification and prosthetics,” it is May who is the monster, not “Amy” (Jones and Harris 525). May’s grossness is related more to what is disturbing than what is disgusting, as is conveyed by her sweet disposition and shy nature. Her affect is uneasiness, but we are not truly disgusted by her until she starts to engage in acts of violence and mutilation.

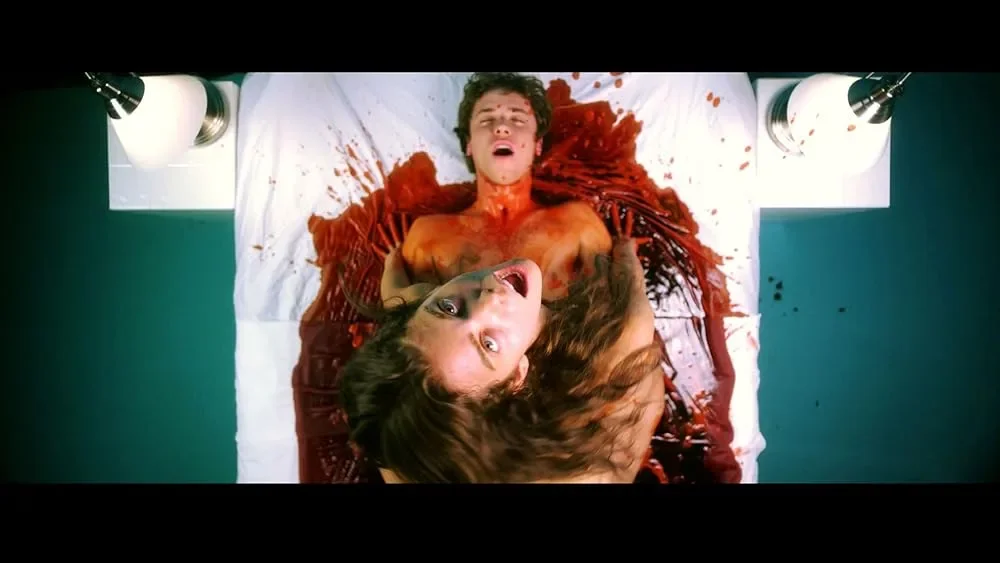

Pauline’s dream sequence in Excision (2012).

Pauline’s grossness, however, is rooted in a desire to be seen as useful, not desirable. With a dream of becoming a medical doctor so she can tend to her sister with cystic fibrosis, she craves the approval of her parents and wants to be recognized for the work she’s completing. Many of Pauline’s actions, though, are incredibly unethical and further complicated by a psychosexual obsession with blood and viscera. Between examining her own blood under a microscope in science class to asking her teacher if one can get an STD from engaging in necrophilia, Pauline is unabashed in her embrace of the abject. She is marred by visceral sexual fantasies, blood-soaked wet dreams that further demonstrate her lack of understanding societal norms. Unlike May, who wants so badly to assimilate with her peers, Pauline is detached from the social intricacies of high school and lets her obsessions with sex, blood, and surgery take the reins. However, these abject thoughts do not make us hate Pauline. Instead, her taboo personage “humanizes, and perhaps even encourages, viewers to ... call out the limitations and censorship placed on human bodies, sexuality, and desires” (Williams 94–95).

It is notable that Pauline does not start out this nonconforming. There are brief glimmers in the film where she desires the same things as her peers: losing her virginity, having friends, and bonding with her sister. As the “more conventional routes to female adulthood have only resulted in her infantilisation and loss of agency,” Pauline abandons traditional moduses of womanhood as a final effort for anyone to take her seriously (d’Hont 25). While May tries to integrate into the strictures of femininity, albeit poorly, Pauline neglects them entirely. Both young women, though, are meant to repulse us in their general demeanor. Even when played by traditionally attractive actresses, girls like Pauline and May are made to make us shudder.

What is striking, though, is that both of these young women physically survive their respective films, but have effectively shattered what’s left of their minds. May is happy to live in blissful ignorance that her new best friend is the sum of her crimes, and Pauline believes she is doing a remarkable job of replacing her sister’s lungs until she takes a final, crying breath at the film’s close, only then realizing what she has done. They do not meet a retributive end. They do not get the glory of escape. Their stories simply end. Perhaps that is the grossest part of all for May and Pauline: Rather than meeting a demise as violent as their crimes, we as an audience must sit in limbo and wonder if they will ever be held accountable for their wrongdoings.

Conclusion: Grossness as a Transgressive Act

Female mutilators, gross girls, monstrous women: The idea that a woman can be so repulsive is in itself subversive. While disgust is a subjective feeling, abjection is an objective concept. The audience may experience different affects, but there will always be the overarching cultural schema that this is not how good girls behave. That is the true horror of the gross girl, that she is the aftermath of “the revulsion and discomfort felt among viewers and critics ... symptomatic of ongoing cultural anxieties regarding female bodies” (Williams 97). She rebels against what is expected of womanhood through perverse applications of sex and death, two absolutes complicated by her deviant ways. Rather than keeping sweet, she lets the world feel her sour rage with every suture and stab.

The horror genre benefits from the presence of gross girls because they encourage sympathy for the profane. All of the atrocities that May, Pauline, and the girls like them in horror cinema commit are even more disturbing when we feel bad for the girls. We watch their changing bodies, their social rejections, and their ostracization from the mainstream; and we feel awful for them. Even though we may not agree with the ways they cope with profound traumas or social isolation, we can understand why they would resort to such circumstances, which in itself is a terrifying feeling to swallow.

What is horror without ugliness, without the desire to turn away but still peer through our spread fingers at the killing thing? The female mutilator extricates herself from the judgment of the world around her by embracing the madness and filth instead of trying to fight against it. A beautiful, unattainable, well-adjusted girl has her affect, but she does not represent the abject we often crave with the genre. As recent horror scholars “deliberately deconstruct the ‘othering’ of the female body in a knowing gesture ... complicating the representation of the subjects and bodies once abjected,” gross girls remain difficult to pin down and dissect, their abjection caused by more than pure madness (Aldana Reyes 403). Positioning these young women in the canon of abjectified beings only solidifies their importance to the genre. Without girls like May and Pauline, we risk losing one of horror’s most necessary affects: empathy.

-

Aldana Reyes, Xavier. “Abjection and Body Horror.” The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Gothic, edited by Clive Bloom, Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, pp. 393–410.

Bates, Richard, director. Excision. Anchor Bay Entertainment, 2012.

Creed, Barbara. “Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection.” The Monster Theory Reader, edited by Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, University of Minnesota Press, 2020, pp. 67–76.

———. “Queering the Monstrous Feminine.” Return of the Monstrous Feminine: Feminist New Wave Cinema, Routledge, 2022, pp. 111–126.

d’Hont, Coco. “Not Your Average Teen Horror: Blood and Female Adolescence in Richard Bates’ Excision (2012).” Comparative American Studies: An International Journal,vol. 16. nos. 1–2, 2018, pp. 18–30.

Fradley, Martin. “‘Hell is a Teenage Girl?’: Postfeminism and Contemporary Teen Horror.” Postfeminism and Contemporary Hollywood Cinema,edited by Joel Gwynne and Nadine Muller, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 204–221.

Jones, Stacy Holman, and Anne Harris. “Monsters, Desire and the Creative Queer Body.” Continuum, vol. 30, no. 5, 19 July 2016, pp. 518–530.

McKee, Lucky, director. May. Lions Gate Films, 2002.

Rapoport, Melanie. “Frankenstein’s Daughters: On the Rising Trend of Women’s Body Horror in Contemporary Fiction.” Publishing Research Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 4, 19 Oct. 2020, pp. 619–633.

Stopenski, Carina. “Exploring Mutilation: Women, Affect, and the Body Horror Genre.” sic: Journal of Literature, Culture, and Literary Translation, vol. 12, no. 2, 19 June 2022, pp. 1–19, https://doi.org/10.15291/sic/2.12.lc.1.

Williams, Lisa Ellen. “‘When I Lose My Virginity, I Want to Be on My Period’: Kink, Abjection, and Female Adolescent Sexuality in Contemporary Cinema.” Binding and Unbinding Kink: Pain, Pleasure, and Empowerment in Theory and Action, Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2023, pp. 87–98.

Article by Carina Stopenski

Carina Stopenski (they/them) is a writer, librarian, and teacher based in Pittsburgh, PA. They are currently pursuing their PhD in English, Literature and Criticism at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Carina is the author of the transgressive fiction collection The Things We Do for Blood (Alien Buddha Press, 2024), the Appalachian folk horror novel Stuffed (Unveiling Nightmares, 2024) and the horror poetry collection feel it in your guts (Baynam Books Press, forthcoming 2026). They are an academic member of the Horror Writers Association, where they currently serve as a member of the Library Advisory Council and co-chair of the Pittsburgh chapter.

Horror, besides being entertaining, is also a powerful tool for raising awareness, reflecting both individual and collective fears and concerns. While every country has its own horror manifestations, this essay focuses on Mexico because of its unique and unsettling relationship with horror. This relationship is analyzed under the term “mexplatterpunk.”