Fracturing Identity: Self-Injury and Societal Violence in ‘The Substance’

Warning: Spoilers for The Substance and discussion of self-harm.

Pitched as a feminist body horror film, I was wholly unprepared for The Substance to be a tearjerker. Beneath the copious gore and fiendish humor, exists a tragic story of the dangerous effect of unattainable social standards on an individual’s self-worth. Through the violent internalization of beauty ideals, self-esteem is ravaged by the oppressive media landscape, exploring the complexities of power and victimhood particularly in the context of self-mutilation.

The Substance first introduces us to Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), a television host of a fitness show, while she walks down a hallway lined with promotional posters commemorating her decades-long career. Each poster photographed Elisabeth in a specific year, so we watch her age with every progressing poster. Her smile fades as she moves down the hallway, the posters taunting her, confronting her with evidence of her aging body. Looking increasingly forlorn, she is interrupted by a coworker telling her, “Happy Birthday!” and letting her know that her boss (Dennis Quaid) would like to speak with her.

“Life stops at 50,” Elisabeth’s boss informs her while tossing back fistfuls of shrimp on their subsequent lunch meeting. He then promptly fires her, ending her career on her 50th birthday. Faced with career extinction, desperate but determined, Elisabeth procures the substance—an experimental drug whispered about in half-baked advertisements purporting to make you a “younger, more beautiful, more perfect” version of yourself. When she injects herself with the substance, her body violently splits open and horrifically births a younger version of herself.

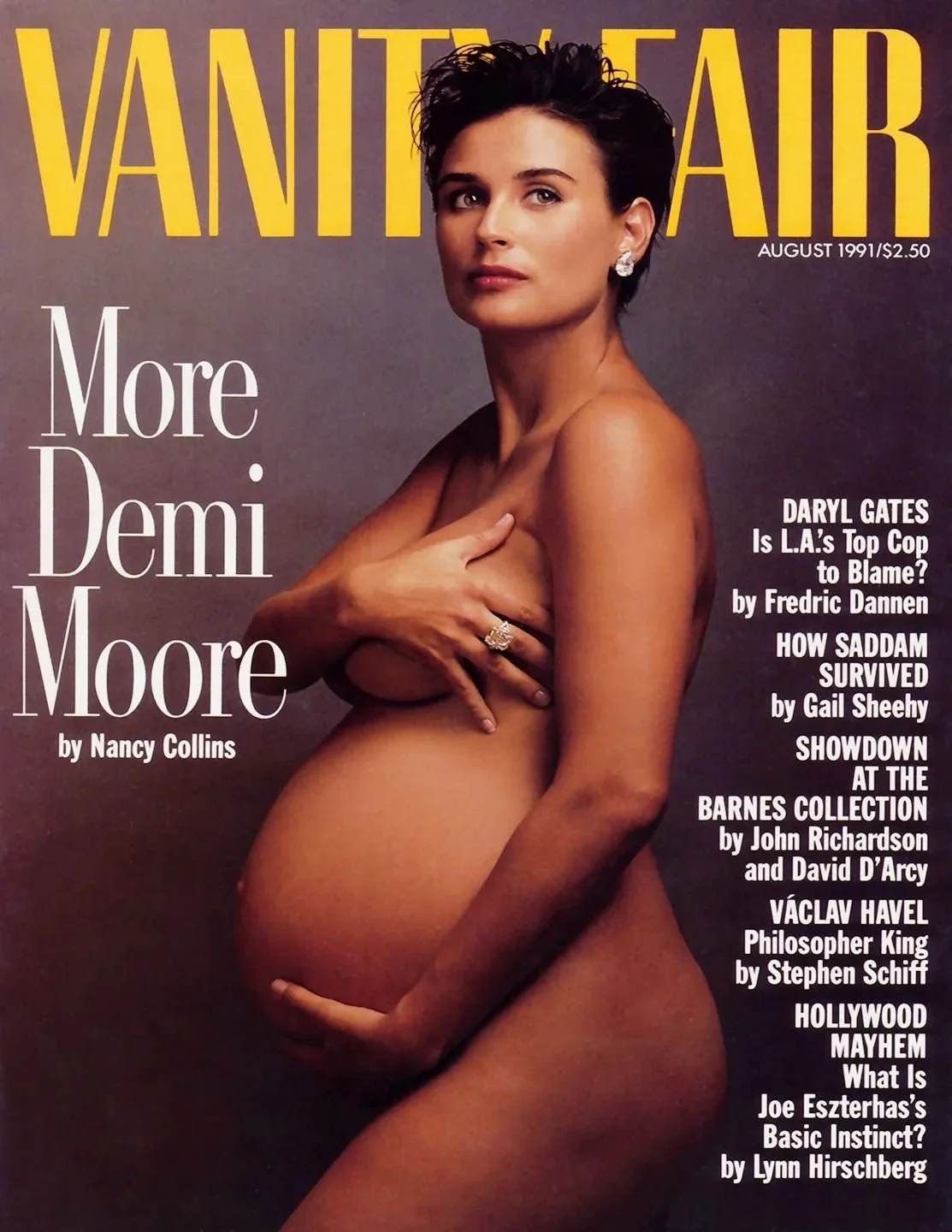

The Substance writer-director Coralie Fargeat chose the most famously pregnant woman in recent history to portray this excruciatingly painful birthing scene. Bathed in soft light, posed demurely, with the caption “More Demi Moore,” Demi Moore’s naked, pregnant body is immortalized in the public consciousness after the infamous 1991 cover of Vanity Fair. Although there was ample criticism and backlash against the cover, the public also celebrated her pregnant body to an unprecedented extent—her beauty almost seeming able to topple long-held social stigmas. The cover even spurred other women such as Britney Spears, Beyonce, Cardi B, and Brooke Shields to grace magazine covers flouting fully pregnant bodies in the following years. Prior to the publishing of this cover, there was an invisibility of pregnant bodies in popular media and shame around pregnancy. Pregnant women were expected to hide their bodies, be more modest, and relinquish their sexuality for their child’s sake. Because of the taboo quality of female pregnancy and birth, our fear becomes ripe territory to explore in horror films such as The Brood (featuring a massive external womb) or in Aliens (featuring a deathly birth cavern) and now The Substance. The proliferation of magazine covers spotlighting pregnant women coupled with the continuing production of gruesome birth scenes in horror films perhaps comments on our growing acceptance of the image of the pregnant body in comparison to our lingering fears of the inner workings of female anatomy.

Directly following the birthing process, Elisabeth’s nude body lies splayed on the bathroom floor, back entirely ripped apart, with a mysterious figure lying beside her. (As originally foreshadowed by the Vanity Fair cover, we have in fact received “More Demi Moore”.) The newer half dubs herself Sue (Margaret Qualley) and proceeds to almost instantly win back Elisabeth’s job with ease. As part of the bargain, Elisabeth can only become Sue every other week. Sue lies inert and motionless when Elisabeth is active and vice versa. Sinking further into the depths of depression, Elisabeth barely leaves the house during her weeks because she continues to feel that her life as a 50-year-old woman is meaningless. She binges on food, wallows in self-pity, isolates herself at home, and waits for Sue to take the wheel. Elisabeth only catches glimpses in half-remembered dreams of her life as her alter ego Sue; she watches her other life from afar in TV show appearances and billboard ads.

In a particularly devastating scene, Elisabeth struggles to leave the house to go on a date. Prior to her scheduled outing, she stands in front of the mirror, perfecting her makeup and outfit. Although the viewer undoubtedly sees her as a glamorous woman, Elisabeth looks at herself in the mirror with growing dissatisfaction. In an effort to improve her appearance, she begins rearranging her outfit and changing her makeup. Suddenly, the need to be perfect erupts in a frenzy, with Elisabeth frantically clawing at her face. Ultimately, she is unable to leave the house, defeated and trapped by her low self-esteem.

Fracturing The Self

Agreeing that Elisabeth’s life is worthless, Sue begins breaking the one-week rule. Sue steals more and more days from Elisabeth, withering, aging, and disfiguring Elisabeth’s body with each transgression. Sue’s career skyrockets at Elisabeth’s expense, booking coveted career milestones at a rapid pace such as a Vogue cover and a gig hosting the New Year’s Eve special. Sue’s version of Elisabeth’s fitness show becomes sexualized to an absurd extreme during her tenure as host. It becomes an exercise show only by title, totally unusable if someone actually wanted to learn a workout routine. It is a compilation of closeups of writhing body parts, meant to appear tantalizing, but oddly repulsive and uncomfortable in effect. The mashup of body parts is more akin to pulsating slabs of meat. The Substance evokes this dual power of skin to “signify beauty and abjection at once, or evoke attraction and repulsion simultaneously… skin doth fester and flower” (Cavanagh et al. 1).

Through taking the substance, Elisabeth has fractured her identity into two halves—much like in the gothic horror novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, which is reimagined in The Substance. Rather than a deal with the devil, Elisabeth becomes a test subject for a nameless company. Rather than a painting, a flesh and blood person bears the consequences, giving a more visceral and sympathetic lens to the self deemed as “ugly.” Both stories speak to a public and a private version of oneself and how societal conventions force them into altering their outward appearance. Moreover, Dorian Gray and Elisabeth Sparkle are both haunted by depictions of themselves.

While Dorian is able to lock his painting in the attic, Elisabeth is doomed to be tortured daily by her own likeness. In modern times, we are inundated with images, cursed with a multitude of means to depict ourselves beyond the painted portrait. It is impossible to hide from images of yourself. In The Substance, Sue and Elisabeth are often viewed as images and videos (such as TV show appearances, billboard advertisements, posters, magazine covers, etc.) rather than in their bodied forms. Elisabeth’s negative self-image spurs increasing anxiety and eventually attacks on videos and photographs of herself:

(1) A dismayed Elisabeth is stalked down the hallway by an unrelenting succession of posters of herself.

(2) Her own reflection in the mirror becomes an image that is impossible to bear.

(3) Elisabeth’s apartment window stares directly at a billboard of Sue posed seductively in her exercise leotard. The billboard plagues Elisabeth throughout the film until she covers her window with papers to conceal the advertisement.

(4) Elisabeth throws an object at the portrait of herself in the living room, cracking the glass.

(5) Elisabeth hurls food at her television after Sue’s appearance on-screen.

Similar to Elisabeth’s anxiety over these self representations, media depictions of ”perfect” bodies are a specter in all of our lives.

The potentially disturbing effect of constant media exposure is discussed widely. For example, an article in Psychology Today analyzes recent data: “As of 2021 estimates, people now encounter a staggering 4,000 to 10,000 advertisements daily. A substantial, yet unquantified, portion of these advertisements features white, thin, and sexualized human models” (Yilmam). Furthermore, whistleblower Frances Haugen “demonstrated a direct link between Instagram usage and suicidal thoughts in 13 percent of UK teen girls and 6 percent of American teens” (Yilmam). Elisabeth’s low self-esteem is fostered by the media environment that surrounds her—relating to how representations of idealized bodies create unattainable cultural ideals and cause dangerous mental health issues in our society.

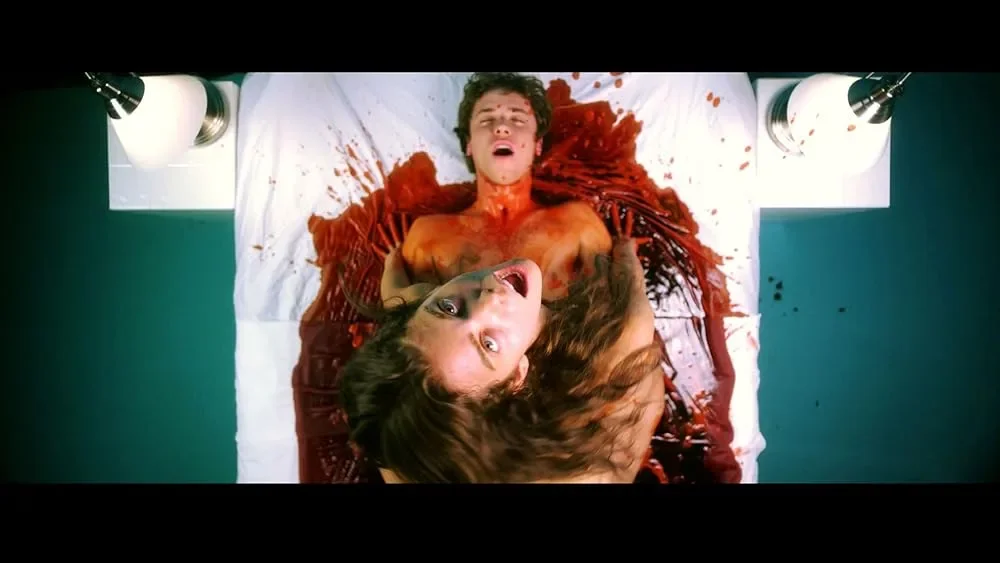

Importantly, though played by two different actresses, Elisabeth and Sue are meant to be seen as one person. The film continually reminds us of such by repeating, “You are you.” In bitter distaste for each other (and themselves), they discard each other’s bodies on the cement floor and leave horrendous messes for each other during their respective comatose weeks. They treat each other with neglect and cruelty, eventually assaulting each other. During a fight, Elisabeth tells Sue, “You’re the only part of me that is still lovable” because she has internalized the societal understanding of an aging woman's body to be unworthy. Sue’s disdain and dismissal of Elisabeth represent this same viewpoint that pressures women to be ever thin, toned, smooth, attractive, and youthful. These demands are only exacerbated in the appearance-obsessed entertainment industry. Driven by personal shame and uncontrollable rage, their fighting escalates into murderous violence.

Mock Vogue cover for The Substance film

Since Sue and Elisabeth are technically the same person, the violence between them can be seen as self-mutilation. Self-injury is so taboo that it is uncommon to be explicitly discussed, even in the horror genre. Speaking in a recent interview, Demi Moore clarified that The Substance is “not about what’s being done to you, it’s about what we do to ourselves” (Oganesyan). Similarly, females are shown to have higher rates of self-harm in national studies. For example, a report by the Centers for Disease Control (that was discussed in a New York Times article) surveyed 65,000 high school students and found, “Up to 30 percent of teenage girls in some parts of the United States say they have intentionally injured themselves without aiming to commit suicide … About one in four adolescent girls deliberately harmed herself in the previous year, often by cutting or burning, compared to about one in 10 boys” (Baumgaertner). Often, women are taught to not voice their feelings directly, so they internalize their emotions, mutilating themselves in an attempt to make their flesh (surface) reflect their feelings (depth). Because of the shame associated with self-harm, these practices often exist invisibly in our society and the corresponding rituals are usually inflicted upon oneself privately. In The Substance, Elisabeth performs painful acts upon herself secretly at home. Her skin is both personally and socially written, her flesh “bears multiple, complex pressures from both within and without…” both felt as “ intimately [her] own, and yet continually shared by encounter and exchange” (Cavanagh et al. 2).

Like the self-injurer, Elisabeth is both victim and perpetrator—representing an ambivalent relationship to agency. Melissa Wilcox describes self-harm’s paradoxical relationship to control in the article “Bodily Transgressions: Ritual and Agency in Self-Injury”:

… while self-injury is controlled violation, it remains violation; it continues to do harm to the body that has already been harmed… Simultaneously with empowering the participant, giving voice to a silenced experience, and placing control back in her or his hands, self-injury literally reinscribes on the body a social power structure of violence and domination (4).

In a further layer of contradiction, her self-harm is performed privately, so Elisabeth’s voice speaks both loudly and quietly. Wilcox explains, “although self-injury gives voice to a silenced experience, it runs the risk of doing so in a vacuum… how powerful is it to give voice when no one is there to hear?” (4). By taking the substance, she retakes control of her body and manipulates her own self-image to achieve her professional ambitions. Concurrently, as the film progresses and Elisabeth’s self-esteem continues to plummet, unaided by the supposed panacea of youth and beauty, it becomes clear that she is both in and out of control of her life. Her bodily manipulations veer into mutilations. She is both Sue and Elisabeth. She is the unconscious body on the ground and the person in charge. She is the actor and the one being acted upon. She plotted a path to survive in a world where “life stops at 50,” but also, she is a casualty of the societal expectations that forced her hand. In this manner, Elisabeth both chooses and has no choice—showing the messiness of agency. She is a relational, but independent being navigating a contradictory world—inundated with media images of flawless bodies coupled with messages to embrace imperfection.

After the most egregious misuse of the substance so far, Sue transforms into an amorphous creature—her body defying her efforts to fulfill traditional feminine roles. In her final monstrous form, she evokes Julie Kristeva’s definition of the abject: her form “does not respect borders, positions, rules.“ it is ”the in-between, the ambiguous, the composite” (4). Liberated from a singular, understandable, and identifiable female form, her violent metamorphosis upsets the societal forces seeking to objectify her body. She becomes boundless.

In a final climactic scene reminiscent of Carrie, the creature ventures to the New Year’s Eve filming set seeking adoration, but is tragically met with ridicule. The creature erupts and sprays the audience with her own blood as they clamor at the doors to escape. This moment is the equivalent of a primal scream. It is an outpouring of unbridled honesty in a scripted life. After so much private suffering, Elisabeth explodes—finally presenting a true image of her pained existence in a public venue. As she spews her insides at the audience, I am reminded of a quote from James Baldwin: “It took many years of vomiting up all the filth I’d been taught about myself, and half-believed, before I was able to walk on the earth as though I had a right to be here.” Once her secret is revealed, she stumbles outside and her body dissolves into a puddle, her fragmented identity at last finding wholeness.

-

Baldwin, James, “They Can’t Turn Back,” History is a Weapon, www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/baldwincantturnback.html. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Baumgaertner, Emily. “How Many Teenage Girls Deliberately Harm Themselves? Nearly 1 in 4, Survey Finds.” The New York Times, 2 July 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/07/02/health/self-harm-teenagers-cdc.html. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Cavanagh, S.L., Hurst, R.A.J. and Failler, A. (Eds.) (2013). “Introduction. Enfolded: Skin, Culture and Psychoanalysis.” In Cavanagh, S.L., Hurst, R.A.J. and Failler, A. Skin, Culture and Psychoanalysis (pp.1-15). Houndmills (UK): Palgrave Macmillan.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez, New York, Columbia University Press, 1982.

Liebowitz, Anne. Cover image. Vanity Fair, August 1991, archive.vanityfair.com/article/1991/8/demis-big-moment/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Oganesyan, Natalie. “Demi Moore Reflects On ‘The Substance’ And The ‘Harsh Violence’ That ‘We Do To Ourselves.’” Deadline, 14 Sept. 2024, deadline.com/2024/09/demi-moore-the-substance-violence-beauty-standards-1236088155/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Qualley, Margaret [@isimolady]. “My first Vogue cover ;) Sue @trythesubstance.” Instagram, September 30 2024, www.instagram.com/p/DAipYOlOOwT/?igsh=M2lxZWhkcnJuOXMz. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

The Substance. Directed by Coralie Fargeat, performances by Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley, Mubi, 2024.

Wilcox, Melissa M. “Bodily Transgressions: Ritual and Agency in Self-Injury.” The Scholar & Feminist Online, vol. 9, no. 3, July 2011, sfonline.barnard.edu/bodily-transgressions-ritual-and-agency-in-self-injury/5/. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Yilmam, Pernille. “How Social Media Distorts Our Body Image.” Psychology Today, 2 Oct. 2023, www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/your-brain-on-body-dysmorphia/202310/how-social-media-distorts-our-body-image?amp. Accessed 18 Oct. 2024.

Article by Julia Betts

Julia Betts is a nationally recognized visual artist. Her work explores vulnerability, often addressing how the mind and body respond under duress. Julia is a lifelong horror fan. Her favorite movies include Invasion of The Body Snatchers, The Thing, Rosemary’s Baby, and Carrie. You can view her work and learn more about Julia at https://www.juliabetts.com/

Horror, besides being entertaining, is also a powerful tool for raising awareness, reflecting both individual and collective fears and concerns. While every country has its own horror manifestations, this essay focuses on Mexico because of its unique and unsettling relationship with horror. This relationship is analyzed under the term “mexplatterpunk.”